DNA Detectives: New ways to spot Southern Ocean hitchhikers

Every living organism sheds its DNA into the environment, leaving a record of its presence. Photo: Matt Low / AAD

Springtails, found in moist soil and leaf litter on Macquarie Island, could gain a foothold in East Antarctica, due to climate change and human activity. Strict biosecurity measures and eDNA play a role in preventing such incursions. Photo: Aleks Terauds / AAD

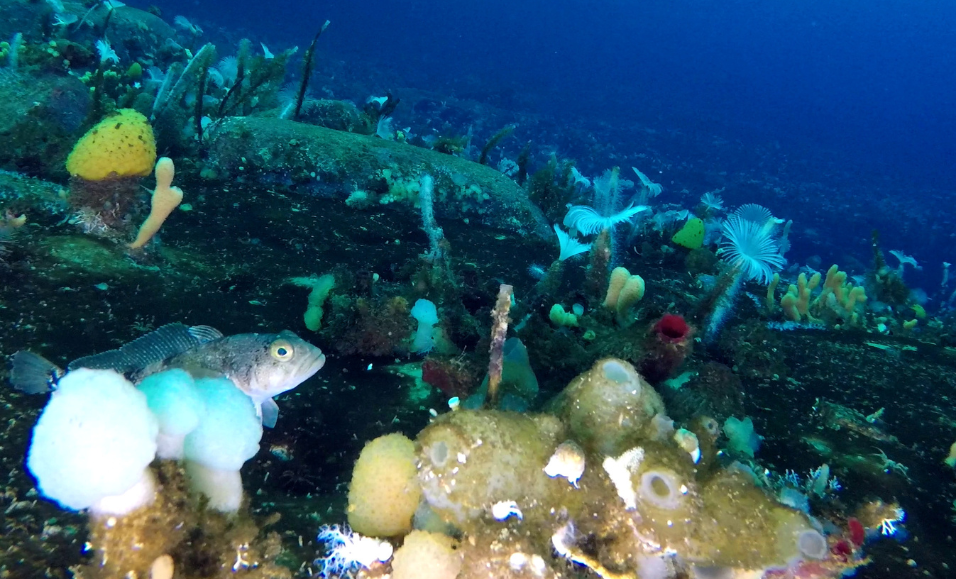

eDNA can be used to distinguish between native Antarctic biodiversity and non-native invaders. Photo: AAD / AAD

An international team of scientists are looking for new methods to defend the frozen continent from alien invasion.

Every living organism sheds its DNA into the environment, leaving an invisible record of its presence.

Now a new paper has examined how this environmental DNA (eDNA) could be used to bolster biosecurity surveillance in East Antarctica.

Ocean-going aliens

Co-Lead author Dr Anna MacDonald from the Australian Antarctic Division said the first task was for a panel of scientists to rank non-native species that posed potential risk to East Antarctica.

“The question we asked was, ‘what plants and animals do you think are the biggest concerns, based on species that have a capacity to reach Antarctica and potential to become established once there?’” Dr MacDonald said.

“We didn’t identify specific species but instead, broader groups, such as mussels and grasses. Now we can use this information to develop new genetic tools for biosecurity monitoring for those groups of concern.”

Strict biosecurity screenings are already in place in Australia and at research stations. But sea stars, mussels, springtails and ascidians (sea squirts) could gain a foothold in East Antarctica due to climate change and human activity.

Scanning a barcode

Co-lead author Dr Laurence Clarke from the Australian Antarctica Division said for eDNA surveillance to work, better DNA data or ‘barcodes’ would be needed to tell the difference between the locals and the gate crashers.

“It’s quite possible there are some Antarctic plants or animals that have a similar DNA sequence or barcode to non-native things we’re trying to stop,” Dr Clarke said.

“If we don’t know what’s down there, we run the risk of getting a DNA sequence that could end up being a false alarm.

“So having reference barcode sequences of native Antarctic species on file is important.”

How it works?

For marine environments, scientists can detect eDNA in water samples.

On ice-free areas of land, scientists can identify eDNA in soil samples, or screen food and station supplies.

Importantly, eDNA could also be used to detect ‘biofouling’ on ships’ hulls in Australia, and potentially Antarctica, where species could cling to the hulls of vessels. It could also detect species transported via footwear or in plane or ship cargo.

What lies beneath?

The paper highlights the need for more research to understand terrestrial and ‘benthic’ (seabed) life along the East Antarctic coast.

Co-author Dr Mark Stevens a Partner Investigator with SAEF from the South Australian Museum said:

“Biosecurity surveillance will become increasingly important going forward if we are going to protect Antarctic ecosystems from non-native species, and eDNA metabarcoding is key to achieving this goal.”

“Luckily, efforts to generate DNA reference libraries by the International Barcoding of Life started 20 years ago and the development of eDNA barcoding have placed us in an excellent position to undertake the management strategies we have put forward in this study.”

Cataloguing the plants and animals that make up the biodiversity of Antarctica and its surrounding waters and understanding how these unique communities are changing in response to threats, including from invasive species, will be a critical element of monitoring undertaken by the Australian Antarctic Division and others in East Antarctica.