This summer, a team of four SAEF scientists travelled into the vast wilderness of Antarctica in search of its tiniest life. Once found, these microscopic creatures will enable the team to answer big questions about the evolution of the continent’s landscape and biodiversity.

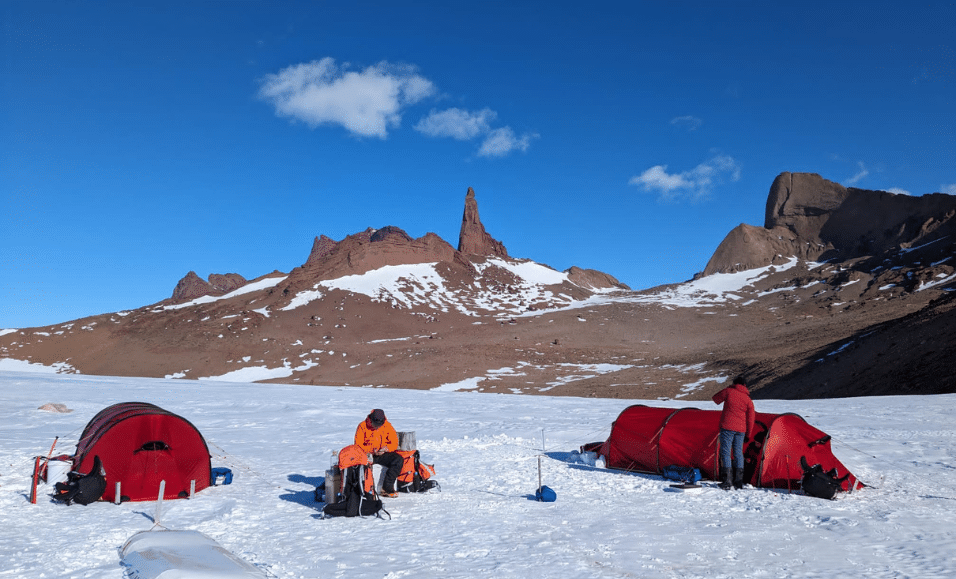

With the support of White Desert, the team travelled to Dronning Maud Land to conduct fieldwork in the Schirmacher Oasis and Holtedahl Mountains. Both regions feature so-called “islands in the ice”, ice-free rocky outcrops and mountain peaks that tower above the surrounding white landscape.

Less than 1% of the continent is ice-free, and these areas are hotspots for Antarctic biodiversity, including microbes, invertebrates, moss and lichen. But scientists don’t yet fully understand what species live there and how they have adapted to survive in such extreme conditions, especially as the continent’s climate and environment have changed over millennia.

But understanding this is one of the keys to their protection and survival.