World’s largest ice sheet is more at risk than we thought.

Scientists overlooking the edge of Mawson Glacier, East Antarctica. Photo: Richard Jones

Snow-blowing across the terminus of Vanderford Glacier, Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Photo: Richard Jones

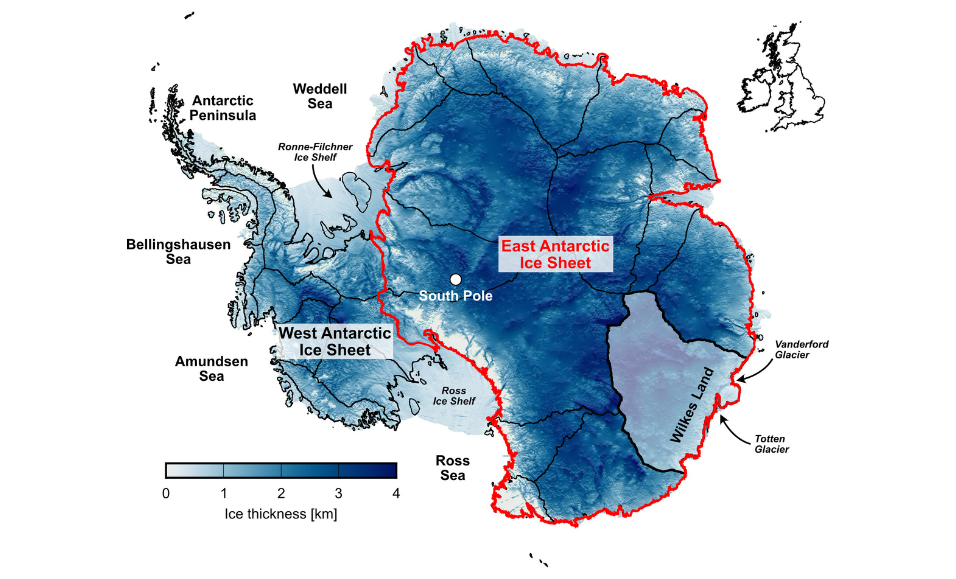

Thickness of ice in Antarctica, showing the location of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (red outline), which holds the equivalent of 52 metres of sea level rise (alongside the UK and Ireland at the same scale). Credit: Guy Paxman, Durham University

Sky over Vanderford Glacier, Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Photo: Richard Jones

This effect, combined with contributions from Greenland and West Antarctica would threaten millions of people worldwide who live in coastal areas.

The study was conducted by an international team of scientists, including Australian experts from two Australian Research Council Special Research Initiatives into Antarctic Science, Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) and the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS). It was led by Professor Chris Strokes at Durham University.

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet

Australia has strong links to the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) as it is where Australia’s research stations Casey, Davis and Mawson are located and where the Australian Antarctic Program conducts most of its scientific fieldwork. It’s also large–nearly 80% of the size of Australia.

“The EAIS has always been considered less vulnerable to climate change than the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and is typically overlooked as a potential source of sea-level rise,” explains Dr Richard Jones, Chief Investigator at SAEF at Monash University who was a co-author on the study.

“It contains the equivalent of 52 metres to global sea level rise, so it is crucial we understand how it will respond to future change.”

Past, present and future change

To assess the sensitivity of East Antarctica to climate change, the scientists looked at how the ice sheet has responded to past warm periods when carbon dioxide concentrations and atmospheric temperatures were only a little higher than at present. They also examined where changes are currently occurring by studying the mass input (mostly via snowfall) and the mass output (mostly via melting ice, and the calving of icebergs).

The team then analysed projections made by previous studies to examine the effects of different emission levels and temperatures on the ice sheet by the years 2100, 2300 and 2500.

On thin ice

SAEF’s Dr Richard Jones led the section of the study that looked into how Antarctica responded to a period of past warming.

“Looking to the geological past, we found that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet was not as stable as previously thought. Large areas of the ice sheet retreated during warm periods similar to today, resulting in multiple metres of sea-level rise,” said Dr Jones.

“The rate of ice loss observed today is similar to what happened during retreat after the last ice age 20,000 years ago. But there are signs that some parts of the ice sheet might be beginning a more dynamic retreat due to ocean warming.”

“Future ice loss—and corresponding sea-level rise—will depend on how much the ocean melts ice at the coast versus how much extra snowfall will occur on top of the ice sheet.”

Future projections

Through their modelling analysis, the scientists found that dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions and keeping warming to below 2°C would see East Antarctica contribute around 2 cm by 2100 and below 50 cm by 2500 to global sea-level rise. This is much less than the loss expected from Greenland and West Antarctica. They also found that any mass loss due to global warming will be offset by increased snowfall over the ice sheet.

However, if the world continues on the pathway of very high emissions, with a temperature increase above 2°C, East Antarctica could potentially contribute several metres to sea-level rise in just a few centuries. This includes nearly half a metre by 2100, 1-3 metres by 2300 and 2-5 metres by 2500.

Don’t put action on ice

“Multi-metre sea-level rise from East Antarctica over the coming centuries can be avoided, but only if we keep global warming to below 2°C as established in the Paris Agreement,” said Dr Jones.

With global mean temperatures already at 1.1°C above average since pre-industrial times, this research is yet more evidence that our window of opportunity to avoid the worst impacts of climate change is quickly closing.

The international research team was led by Professor Chris Stokes (Durham University) and includes Australian-based scientists Richard Jones (Monash University), Nerilie Abram (Australian National University), Matthew England (University of New South Wales), Matt King (University of Tasmania) and Annie Foppert (University of Tasmania). The Australian scientists include members of the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP) as well as two Australian Research Council Special Research Initiatives into Antarctic Science: Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future (SAEF) and the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS).

Paper

Chris R. Stokes, Nerilie J. Abram, Michael J. Bentley, Tamsin L. Edwards, Matthew H. England, Annie Foppert, Stewart S.R. Jamieson, Richard S. Jones, Matt A. King, Jan T.M. Lenaerts, Brooke Medley, Bertie W.J. Miles, Guy J.G. Paxman, Catherine Ritz, Tina van de Flierdt, Pippa L. Whitehouse. (2022). Response of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet to Past and Future Climate Change. Nature. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04946-0