Dr Jones and the Rock of Destiny

Another way the expedition will help scientists better predict future change in Antarctica is by offering a window into how the Denman Glacier has changed over past millennia.

Dr Jones says that the glacier has retreated over 5 km in recent decades, “We don’t know whether this is normal or the start of a worrying new trend.” At what points was it retreating, stable, and advancing, and what were the associated climatic conditions?

He and his Monash University team, including Dr Levan Tielidze and PhD students Jacinda O’Connor and Corey Port, were on a mission to collect glacial rocks, lake mud, and beach sand—useful archives that offer a window into past glacier change.

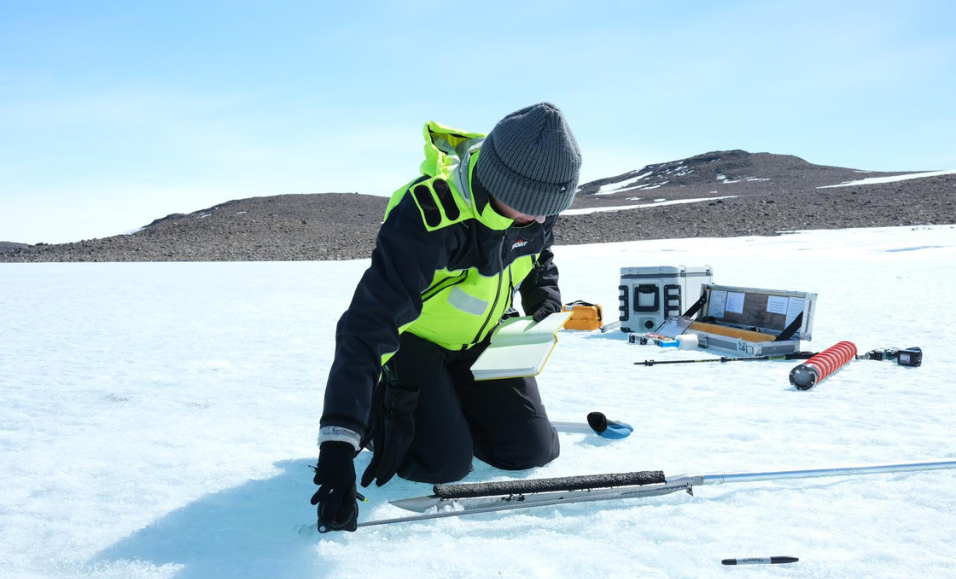

The beach sand and lake mud record past sea level change. The team collected the former by digging pits into a sequence of terraces along pebbly bay shores, while to collect the lake mud, the team needed to drill through 2 to 3 metres of lake ice and then push their corer through another 1 to 3 metres of water to reach the lake bottom where they could pull up rich and darkly layered cores.

Meanwhile, alongside the Denman Glacier, nunataks, which are mountains that protrude through the surrounding ice, offer rock samples that record glacier thickness change.

“These rock samples are useful as they essentially act as stopwatches,” Port explains, “recording the time since they were uncovered via the accumulation of cosmogenic isotopes – chemical signals that are produced within minerals contained in the rock (such as quartz) by cosmic ray bombardment.”

“By understanding the concentration of cosmogenic isotopes in samples at different elevations, we can understand how the glacier has thinned over time.”

When the team arrived at a site, they would traverse to the closest point of the nunatak to the ice, looking for potential samples along the way and evidence of glacial erosion, such as scratch marks and lack of weathering. They would then work their way back up the nunatak, collecting samples every 5 – 10m of elevation, using angle grinders, rock corers, hammers, and chisels.

“Along the way our packs would get heavier, and the whole thing became a race against time. When would that helicopter be picking us up? Sometimes a lot earlier than planned!” Port says.

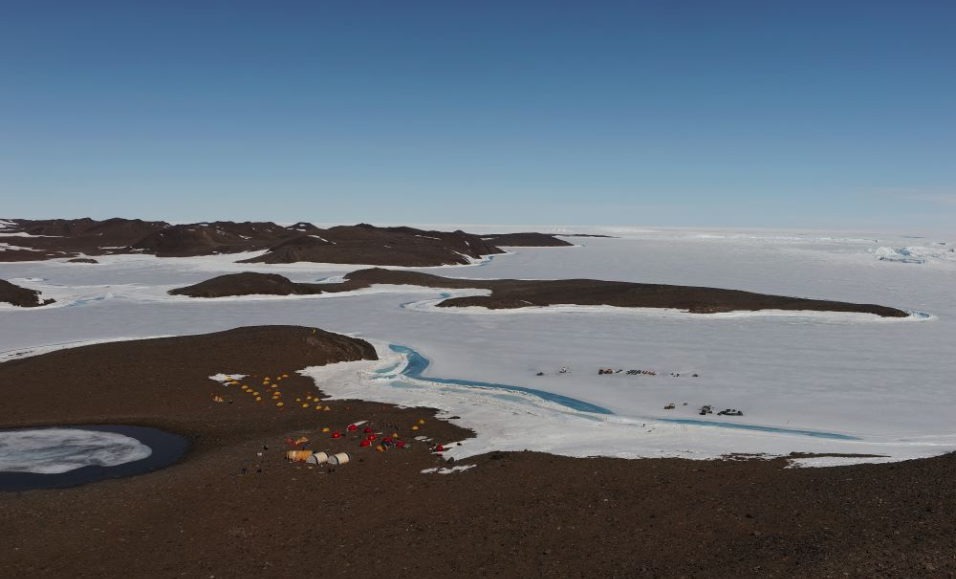

Before their departure south, the team spent hours poring over maps and satellite imagery trying to understand the landscape they would eventually set foot upon. “Although we quickly found out that satellite imagery is a poor substitute for being there on the ground!” Port says.

The locations the team visited were much more dramatic and challenging than they’d anticipated, and the conditions differed at each.

“Cape Jones, where we spent a glorious week, felt tropical (to Antarctic standards!) Katabatic winds would blow throughout the night and in the early morning, but eventually, these would die down and leave us with still, sunny days,” says Corey.

“Further upstream along the Denman Glacier stood Mt Strathcona and Mt. Barr-Smith. Attempts to reach their heights were often canceled by winds exceeding 50 knots, which are especially perilous along Strathcona’s steep cliffs and high elevations.”

“When ‘good’ days came around and we made it up there, winds were still biting cold and unwavering. I recall attempting to turn my back to the wind to get a reprieve from the snow for a moment, but the wind would circle around my back and blow the snow back at me.”

“Despite the weather, the views at both these sites were spectacular and dramatic, truly an Antarctic experience.”

This phrase was used by several scientists, particularly in relation to the extreme and unpredictable weather. On one particular day, Dr Jones and O’Connor were out doing some surveying when the weather suddenly turned. In blizzard conditions, it took them an exhausting four hours to hike back to camp. Dr Clarke, Phillips, and Dr Travers also spent an unplanned night out when the weather suddenly deteriorated, and the helicopter was unable to pick them up. Clarke says, “It was windy and snowing but the camp was actually quite fun, especially given that we were safe, and eating lots of chocolate from the survival kits.” A true Antarctic adventure.

While the team had great weather in December, this didn’t last into January, which meant that they had to adjust the scope of their work and devise alternative plans.

“Luckily, part of our planning was coming up with priorities and backup plans, and more backup plans. In saying that more backup plans were eventually made in the field, as the realities of working in an extreme environment and being subservient to the whims of the weather became apparent,” says Port.

Fortunately, the team managed to collect samples at all their sites and they have now returned home “happy and exhausted” with 215 kg of rock, 13 lake sediment cores and 20 kgs of beach sand. Now the team has many months ahead of them processing the samples in the lab and analysing the data in the offices to unveil the glacier’s history.