New research reveals how Antarctica’s tiny non-ice-dwelling species survived the ice age

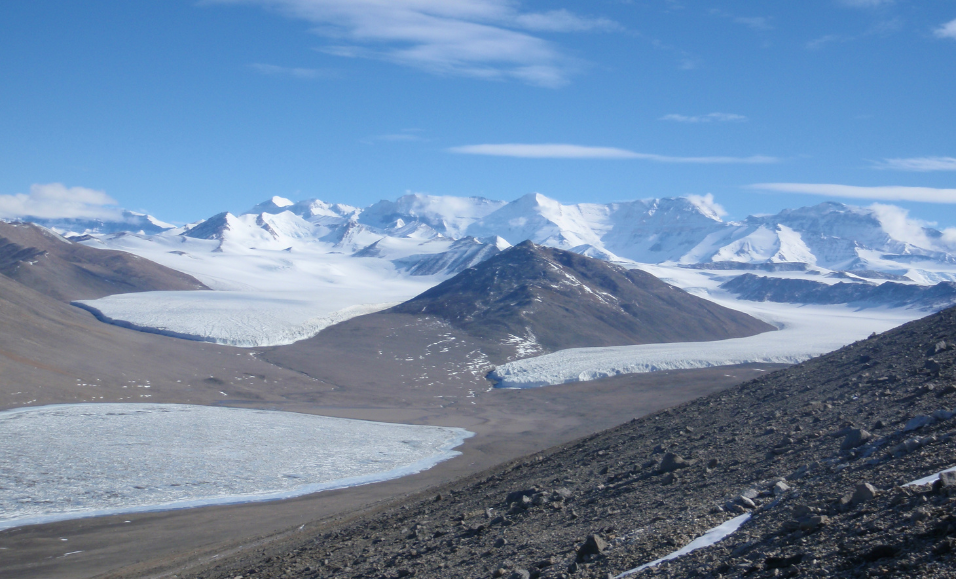

Looking up Miers Valley with the Royal Society Ranges in the background. Credit: Mark Stevens

Springtails from Dronning Maud Land in Antarctica. Credit: Cyrille D’Haese

Sampling on Mawson Escarpment in Prince Charles Mountains. Credit: Paul Czechowski

Dr Mark Stevens overlooking Miers Valley. Credit: Stephen Pointing

At the glacial margin. Credit: Mark Stevens

The research reveals that like moving livestock to higher ground during a flood, these animals survived in ice-free refuges, such as rocky outcrops protruding from ice-covered mountains. They have then expanded their range to their present-day habitats as the ice has retreated.

Senior Research Scientist Dr Mark Stevens from the South Australian Museum explains that this has long been theorised by scientists, but until now they had no evidence to prove it.

“Using the distribution data of Antarctic springtails, tiny animals found in almost every ecosystem on Earth, and “cosmogenic nuclide dating”, a method to tell when a rock was last covered in ice, this research reveals where Antarctica’s tiniest life was able to survive during the last ice age,” said Dr Stevens.

The scientists behind the research are from Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future, an Australian Research Council-funded program. It has a focus on cross-disciplinary science to answer the continent’s biggest questions.

The team undertook the research by examining published ice sheet reconstructions created using cosmogenic nuclide dating to identify where the ice-free areas remained during the last glacial maximum. They then overlaid over 120 years of distribution data of springtail habitats to see how they correlated.

Professor Andrew Mackintosh from Monash University explains that the research highlights the benefits of cross-disciplinary science.

“By using a method developed by geologists to understand how ice sheets respond to climate change, this research reveals a biodiversity response to climate change,” said Professor Mackintosh.

“Today every known species of springtail in Antarctica is found within 100 km of the ice-free areas that remained during the last glacial maximum. These species are also completely absent in current-day ice-free regions that would have been covered in ice.”

So, when you’re tiny, and ice is expanding over your home, how do you survive?

“The highest levels of biodiversity in polar and alpine regions are found in the ice-free areas directly adjacent to glacial ice. The animals that live in these ecosystems move in relation to the glacial margin, potentially because it provides them with access to available water,” explains Dr Stevens.

Professor Mackintosh said that recent modelling shows that ice-free areas in Antarctica may expand by up to 25% by 2100 and that this poses a risk to Antarctica’s biodiversity.

“This research offers new ways of understanding how changes in Antarctic landscapes have shaped the lives of the biodiversity that lives there. Life in Antarctica faces an uncertain future under a changing climate and this research can help us better understand how they might respond.”

Interviews available

- Dr Mark Stevens, Senior Research Scientist, South Australian Museum

- Professor Andrew Mackintosh, Head of School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, Monash University

About the author

Anna Quinn

Anna is SAEF’s the Senior Communications Adviser.